What if it’s Misused?: Why Ethical Imagination Matters in AI Design

In the fall of 2023, a quiet private school in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, became the center of national attention, not for academic excellence, but for a disturbing misuse of technology. Deepfake images had surfaced online depicting several female students in explicit, AI-generated nudes. None of the images were real. But the impact was.

The photos, manipulated with freely available AI tools, were convincing enough to spread rapidly through student group chats and social media. Parents were horrified. Students were traumatized. The school administration scrambled to respond. And the broader community was left asking a chilling question:

What happens when technology outpaces our ability to protect people from its misuse?

This wasn’t a failure of software. It was a failure of foresight.

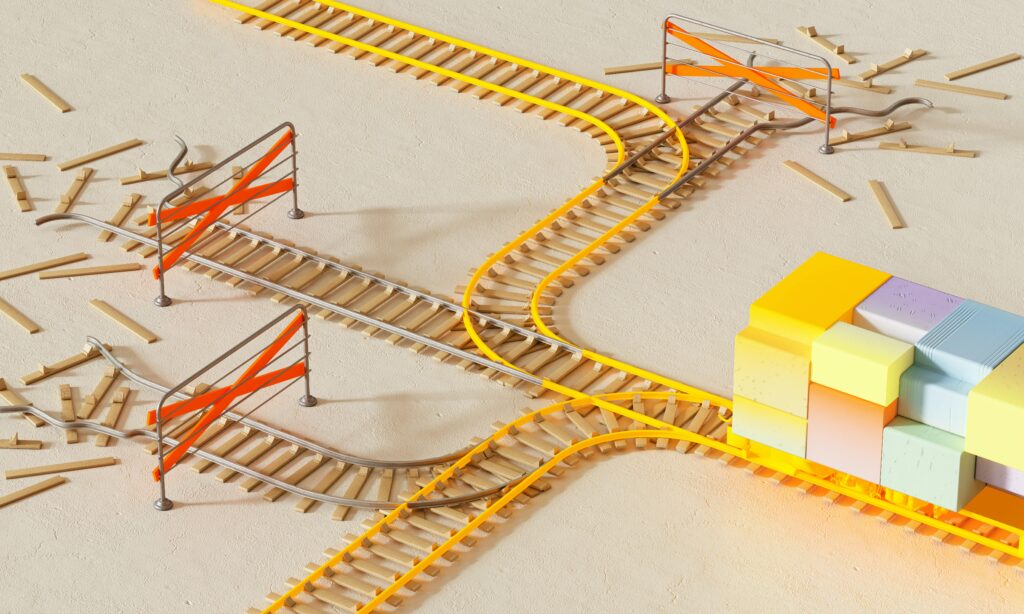

We often think of design as creative problem-solving. But it must also be anticipatory in a world increasingly shaped by generative AI and adaptive systems. Designers aren’t just making things that work, they’re shaping tools that influence behavior, emotion, and even identity. With that power comes a new responsibility: to imagine not only the best-case scenario, but also the worst.

That’s where ethical imagination comes in.

Designing for AI Means Designing for Misuse

In traditional design, edge cases were often framed as bugs to fix. In AI-powered systems, they might be the very things people exploit first.

The deepfake scandal in Pennsylvania wasn’t the result of bad UI, it was the outcome of easily accessible, powerful tools released without guardrails. When anyone can generate hyper-realistic fake images, voices, or text with a few clicks, misuse isn’t hypothetical. It’s inevitable.

As designers, we’re trained to design for intended use. But in the AI era, we also have to design with a sense of plausible misuse.

Why this shift matters:

- AI doesn’t know context. Tools can be co-opted to harass, manipulate, or deceive if safeguards aren’t built in.

- AI moves fast. Once released, even well-intended features can cause ripple effects before you have time to respond.

- AI is opaque. Users (and even builders) don’t always understand how decisions are made, making it harder to catch ethical red flags early.

What ethical imagination looks like in practice:

- Asking not just “Will this work?” but “What could go wrong?”

- Running red-team exercises to test how features might be exploited

- Designing friction intentionally, making harmful actions less convenient, not easier

Real-world examples of overlooked misuse:

- AI beauty filters that lighten skin tones by default, reinforcing colorism.

- AI hiring tools that filtered out candidates with gaps in employment disproportionately affecting caregivers or those with disabilities.

- Chatbots intended for simple support conversations repurposed for unmoderated mental health advice or romantic companionship.

These cases didn’t stem from malice. They came from a lack of imagination, of not thinking far enough ahead, or not widening the lens during the design process.

Ethical imagination means expecting people to be clever, not just in how they use tools, but in how they might misuse them. And building with that expectation from the start.

You Don’t Need to Be an Ethicist to Lead Ethical Design

Many designers hesitate to speak up about ethics because they don’t feel like experts. They’re not ethicists. They didn’t major in philosophy. They don’t write the algorithms. But here’s the truth:

Ethical design isn’t about having all the answers. It’s about asking better questions.

Designers are uniquely positioned to do this. You’re trained to see problems from the user’s perspective. You understand how friction, defaults, and affordances shape behavior. You ask why something exists, not just how it works. That’s the mindset ethical design needs.

Here’s how to lead, even if ethics isn’t your job title:

▶ Frame ethics as a design constraint, not a blocker

When someone says “That’s an edge case,” ask: Is it rare, or just underrepresented in our thinking?

When a product decision raises concerns, reframe the conversation: “Let’s treat harm prevention the same way we treat accessibility, non-negotiable.”

Use the same energy you’d apply to usability bugs or accessibility issues. Ethics deserves a seat at the same table.

▶ Run simple ethical prompts and workshops

You don’t need a PhD to lead a discussion on risk. During sprint planning or feature reviews, try asking:

- What’s the worst that could happen with this feature?

- How might someone misuse it intentionally?

- If this went viral tomorrow, would we be proud of how it behaves?

You can also introduce red-teaming or “pre-mortems” into design critiques to surface issues before they ship.

▶ Use frameworks and tools built for teams like yours

There’s a growing set of designer-friendly tools to make ethical reflection easier:

- Google’s AI Principles – Practical resources, including case studies, tools, and governance frameworks to help teams implement responsible AI

- Microsoft’s Responsible AI Guidelines – Tools, practices, and policies used by Microsoft to uphold responsible AI practices

Don’t overcomplicate it. Start small: Pick one ethical principle and ask how your next feature addresses it.

▶ Create a culture where ethics isn’t awkward

Sometimes the biggest challenge is cultural. Teams avoid talking about harm because it’s uncomfortable or seen as a blocker to speed. But when designers consistently bring ethical imagination into the room, it starts to normalize the conversation.

Saying “We need to talk about potential misuse” doesn’t make you a downer. It makes you a pro.

You don’t need permission to lead on ethics. You just need to be willing to pause, question, and care.

Ethical imagination isn’t a luxury, it’s a core design skill in the age of AI. As systems grow more powerful and unpredictable, the ability to anticipate harm, advocate for users, and design with integrity is what sets great designers apart. You don’t need to be an expert in AI or ethics to lead. You just need to care enough to ask, “What if?”, and be brave enough to act on the answer.